Engelhardt, Unbanning Maus!

My Life with Maus

Or How I Was Banned (Even If in a Second-Hand Way) by a Trumpian World

Sometimes life has a way of making you realize things about yourself. Recently, I discovered that an urge of mine, almost four decades old, had been the very opposite of that of a rural Tennessee school board this January. In another life, I played a role in what could be thought of as the unbanning of the graphic novel Maus.

For months, I’ve been reading about the growing Trumpist-Republican movement to ban whatever books its members consider politically unpalatable, lest the lives of America’s children be sullied by, say, a novel of Toni Morrison’s like The Bluest Eye or Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale or a history book like They Called Themselves the K.K.K. It’s an urge that just rubs me the wrong way. After all, as a boy growing up in New York City in the 1950s, when children’s post-school lives were much less organized than they are today, I would often wander into the local branch of the public library, hoping the librarian would allow me into the adult section. There — having little idea what I was doing — I would pull interesting-looking grown-up books off the shelves and head for home.

Years later, exchanging childhood memories with a friend and publishing colleague, Sara Bershtel, I discovered that, on arriving in this country, she, too, had found a sympathetic librarian and headed for those adult shelves. At perhaps 12 or 13, just about the age of those Tennessee schoolkids, we had both — miracle of miracles! — not faintly knowing what we were doing, pulled Annmarie Selinko’s bestselling novel Désirée off the shelves. It was about Napoleon Bonaparte and his youthful fiancé and we each remember being riveted by it. Maybe my own fascination with history, and hers with French literature, began there. Neither of us, I suspect, were harmed by reading the sort of racy bestseller that Republicans would today undoubtedly loathe.

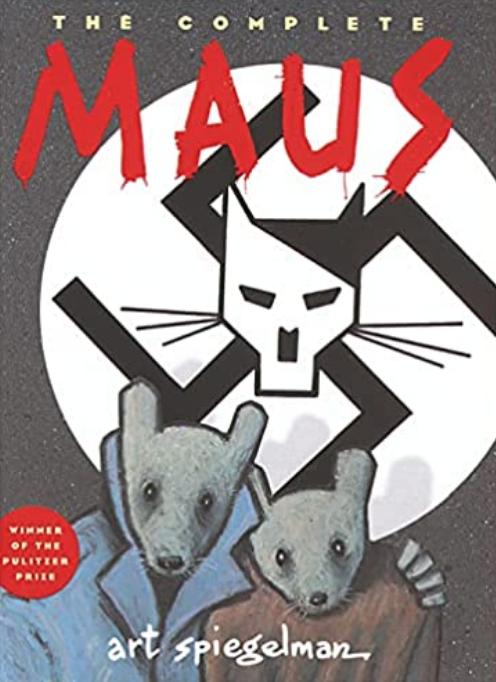

Oh, and if you’ll excuse a little stream of consciousness here, my friend Sara was born in a German displaced-persons camp to Jewish parents who had, miraculously enough, survived the Nazi death camps at Auschwitz and Buchenwald, which brings me back to the jumping-off spot for this piece. Unless you’ve been in Ukraine these last weeks, it’s something you undoubtedly already know about, given the attention it’s received: that, by a 10-0 vote, a school board in McMinn, Tennessee, banned from its eighth-grade classroom curriculum Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel Maus, about his parents’ Holocaust years in Auschwitz and beyond (and his own experience growing up with them afterward). When I first heard about that act I felt, however briefly and indirectly, pulled off the shelves myself and banned. And damn! — yes, I want to make sure that this piece gets banned as well! — I felt proud of it!

Just to back up for a moment: that Tennessee school board banned Spiegelman’s book on the grounds, at least nominally, that it contained naked cartoon mice — Jewish victims in a concentration camp and Spiegelman’s mother, who committed suicide, in a bathtub — and profanity as well (like that word “damn!”). In a world where, given a chance, so many of us would head for the modern equivalent of those adult library shelves — these days, of course, any kid with an iPhone or a computer can get a dose of almost any strange thing on this planet — that school board might as well have been a marketing firm working for Maus. After all, more than three decades after it first hit the bestseller lists, their action sent it soaring to number one at Amazon, while donated copies began to pour into rural Tennessee.

As former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich recently pointed out, if you truly want a teenager to read any book with gusto, the first thing you need to do is, of course, ban it. So, I suppose that, in its own upside-down way, the McMinn board did our world a strange kind of favor. In the long run, however, the growing rage for banning books from schools and libraries (or even, in the case of the Harry Potter books, burning them, Nazi-style) doesn’t offer a particularly hopeful vision of where this country’s headed right now.

“What’s So Funny?“

Still, as I’m sure you’ve guessed, I’m only going on like this because that incident in Tennessee and the media response to it brought back an ancient moment in my own life. So, think of the rest of this piece as a personal footnote to the McMinn story and to the growing wave of book bannings in courses and school libraries across too much of this country. And that’s not even to mention the plethora of “gag order” bills passed by or still being considered in Republican-dominated state legislatures to prevent the teaching of certain subjects. It’s further evidence, if you need it, of an urge to wipe from consciousness so much that they find uncomfortable in our national past. It’s also undoubtedly part of a larger urge to take over America’s public-school system, or even replace it, much as Donald Trump and crew would like to all-too-autocratically take over this country and transform it into an unrecognizable polity, a subject TomDispatch has covered for years.

However, my moment in the sun began at a time when The Donald was about to open the first of his Atlantic City casinos that would eventually turn him into a notorious bankuptee. And it took place inside the world of publishing, which then seemed all too ready to essentially ban Maus from this planet. Back in the early 1980s, putting out a Holocaust “comic book” — though the term “graphic novel” existed, just about no one in publishing knew it — in which Jews were cartoon mice and the Nazis cats, seemed like a suicidal act for a book publisher.

And in that context, here’s my personal story about the cartoon mice that might never have made it to McMinn County, Tennessee. In the 1980s, I was an editor at Pantheon Books, a publishing house run by André Schiffrin who, in a fashion hardly commonplace then or later, gave his editors a chance to sign up books that might seem too unfashionable or politically dangerous.

One day, our wonderful art director, Louise Fili, came to my office. (She worked on another floor of the Random House building in New York City, the larger publishing house of which we were then a part.) In her hands, she had an oversized magazine called RAW that I had never seen before, put out by a friend of hers named Art Spiegelman. It was filled with experimental cartoon art. And in the seams of new issues, he had been stapling tiny chapters of a memoir he was beginning to create about the experiences of his father and mother in the Holocaust. Jews from Poland, they had ended up in Auschwitz and managed, unlike so many millions of Jews murdered in such death camps, to survive the experience. Louise also had with her a proposal from Spiegelman for what would become his bestselling graphic novel Maus.

I still remember her telling me that it had already been rejected by every publisher imaginable. In those days, that was, I suspect, something like a selling point for me. Anyway, I took the couple of teeny chapters and the proposal home — and all these years later, I still recall the moment when I decided I had to put Spiegelman’s book out, no matter what. I remember it because I thought of myself as a rather rational editor and the feeling that I simply had to do Maus was one of the two least rational decisions I ever made in publishing (the other being to do Chalmers Johnson’s book Blowback, also a future bestseller).

At that moment, I doubt I had ever read what came to be known as a graphic novel, but there was something in my background that, I suspect, left me particularly open to it. My mother, Irma Selz, had been a theatrical and later political caricaturist for New York’s leading newspapers and magazines (and, in the 1950s, the New Yorker as well). She was, in fact, known as “New York’s girl caricaturist” in the gossip columns of her time, since she was the only one in an otherwise largely male world of cartoonists.

Because she lived in that world, after a fashion I did, too. I can, for instance, remember Irwin Hazen, the creator of the now largely forgotten cartoon Dondi, sitting by my bedside when I was perhaps seven or eight drawing his character for me on sheets of tracing paper before I went to sleep. (Somewhere in the top of my closet, I suspect I still have those sketches of his!) So I think I was, in some unexpected way, the perfect editor for Spiegelman’s proposal. I was also a Jew and, though my grandfather had come to America in the 1890s from Lemberg (now Ukraine’s Lviv) and later brought significant parts of his family here, I remember my grandmother telling me of family members who had been swallowed up by the Holocaust.

Anyway, here’s the moment I still recall. I was lying down reading what Louise had given me when my wife, Nancy, walked past me. At that moment, I burst out laughing. “What’s so funny?” she asked. Her question took me completely aback. I paused for a genuinely painful moment and then said, haltingly and in an only faintly coherent fashion, something like: “Uh… it’s a proposed comic book about a guy whose parents lived through Auschwitz and later, in his adolescence, his mother committed suicide…”

I felt abashed and yet I had been laughing and that stopped me dead in my tracks. At that very moment, I realized, however irrationally, that whatever this strange, engrossing, disturbing comic book about a world from hell turned out to be, I just had to do it. From that moment on, whether it ever sold a copy or not wasn’t even an issue for me.

A Holocaust Comic Book?

And then, you might say, the problems began. I went to André, told him about the project, and he reacted expectably. Who in the world, he wondered, would buy a Holocaust comic book? I certainly didn’t know, nor did I even care then. In some gut way, I simply knew that a world without this book would be a lesser place. It was that simple.

Thank heavens, as a boss, André deeply believed in his editors, just as we editors believed in each other. He also hated to say “no.” So, instead, a kind of siege ensued while the proposed book passed from hand to hand and others looked and reacted, but I remained determined and knew that, in the end, if I was that way, he would let me do it, as indeed he did.

I was considered something of a fierce editor in those days and yet I doubt I touched a word of Spiegelman’s manuscript. What it is today, it is thanks purely to him, not me. I took him out to lunch to tell him about our publication decision and prepare the way for our future collaboration. While there, I assured him that I knew nothing about producing such a book — he, for instance, wanted the kind of flaps that were found on French but not American paperbacks — and would simply do what he wanted. The one thing I wanted him to know, though, was that he shouldn’t get his hopes up. Given the subject matter, it was unlikely to sell many copies. (A Pulitzer Prize? It never crossed my mind.)

Fortunately, as far as I could tell, he all too sagely paid no attention whatsoever to me on the subject. And as it happened, some months later (as best I remember), the New York Times Book Review devoted a full page to him and, in part, to the future Maus. It was like a miracle. We were stunned and, from that moment on, knew that we had something big on our hands.

And in that fashion, in another century, you could say that I unbanned Maus, preparing the way for McMinn County to ban it in our own Trumpist moment. I couldn’t be prouder today to have had a hand in producing the book that caricaturist David Levine would all too aptly compare to the work of Franz Kafka.

In its continuing eventful existence, as a unique record of the truly terrible things we humans are capable of doing to one another, it is indeed a masterpiece. It raises issues that all of us, parents and children, should have to grapple with on our endangered planet, a place where we have so much work ahead of us if, in some terrible fashion, we don’t want to ban ourselves.

Copyright 2022 Tom Engelhardt

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Books, John Feffer’s new dystopian novel, Songlands (the final one in his Splinterlands series), Beverly Gologorsky’s novel Every Body Has a Story, and Tom Engelhardt’s A Nation Unmade by War, as well as Alfred McCoy’s In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power, John Dower’s The Violent American Century: War and Terror Since World War II, and Ann Jones’s They Were Soldiers: How the Wounded Return from America’s Wars: The Untold Story.