Beverly Gologorsky, What Is Possible?

[Note for TomDispatch Readers: Given that Tuesday is July 4th, the next TD piece won’t arrive until Thursday and, in the meantime, don’t you think that the patriotic thing to do would be to visit the TD donation page and lend us a hand? Tom]

It’s reasonable to ask: What gets anyone involved in politics, American-style? What leads any of us to decide to protest anything? Today, TomDispatch regular (and my old friend) Beverly Gologorsky explores how a childhood in poverty prepared her to become “political” — to become, that is, an “activist against injustice” (as well as a superb novelist).

In comparison, I grew up in what at least passed for a middle-class family in New York City’s Manhattan in the “golden” 1950s. It’s true that my parents were actually having quite a tough time then. I can still remember hearing them loudly arguing — at a moment when I was supposed to be asleep — about how they were going to pay “Tommy’s bills.” Still, I was lucky, relatively speaking, and I was certainly raised to be neither a political activist nor particularly critical of the American world I would find myself in.

Nonetheless, sometime in the 1960s, the distant nightmare of the war in Vietnam got under my skin. Something about what this country was doing in a particularly grim and bloody fashion in that distant land genuinely unnerved me. Why, I’m not quite sure, but — perhaps because, in those years, long before the all-volunteer military, I expected to be drafted sooner or later — I finally found myself in the streets protesting and, in the end, turned in my draft card as an act of resistance. That changed the way I looked at my own country, which led me, however tortuously and decades later, to TomDispatch.

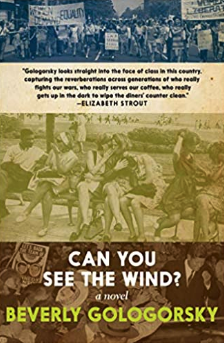

And that, in turn, means, however I explain my personal path into the political, I was here and ready when Beverly offered me her own moving explanation. (And by the way, if you have a chance, I couldn’t recommend more strongly her latest novel, Can You See the Wind?, which — yes — is set in those very years of the Vietnam War.) Tom

How the Personal Becomes Political

Or You Can Fight City Hall

[TomDispatch and StatORec Literary Journal are sharing the publication of this article.]

Looking into the long reflecting pool of the past, I find myself wondering what it was that made me an activist against injustice. I was born in New York City’s poor, rundown, and at times dangerous South Bronx, where blacks, whites, and Latinos (as well as recent immigrants from Ireland, Italy, and Eastern Europe) lived side by side or, perhaps more accurately, crowded together.

I was the middle child of four siblings, not counting the foster children my mother often cared for. My father worked six days a week in a leather factory where the rat-tat-tatting of sewing machines never stopped and layoffs were a constant reality. I grew up after World War II in the basement of a six-story building at a time when jobs were still hard to find and scary to lose. Many young men (really boys) joined the military then for the same reason so many young men and women volunteer today, one that, however clichéd, remains a reality of our moment: the promise of some kind of concrete future instead of a wavy unknown or the otherwise expectable dead-end jobs. Unfortunately, many of them, my brother included, returned home with little or nothing “concrete” to show for the turmoil they endured.

At the time, there was another path left open for girls, the one my parents anticipated for me: early marriage. And there was also the constant fear, until the introduction of the birth-control pill in the 1960s, of unplanned pregnancies with no chance of a legal abortion before Roe v. Wade. After all, dangerous “kitchen-table” abortions — whether or not they were actually performed on a kitchen table — were all too commonplace then.

Poverty, Burned-out Buildings, Illness, and Crime

Yet growing up in the South Bronx wasn’t an entirely negative experience. Being part of a neighborhood, a place where people knew you and you knew them, was reassuring. Not surprisingly, we understood each other’s similar circumstances, which allowed for both empathy and a deep sense of community. Though poverty was anything but fun, I remain grateful that I had the opportunity to grow up among such a diversity of people. No formal education could ever give you the true power and depth of such an experience.

The borough of the Bronx was always divided by money. In its northern reaches, including Riverdale, there were plenty of people who had money, none of whom I knew. Those living in its eastern and western neighborhoods were generally aiming upward, even if they were mostly living paycheck to paycheck. (At least the checks were there!) However, the South Bronx was little more than an afterthought, a scenario of poverty, burned-out buildings, illness, and crime. Even today, people living there continue to struggle to eke out a decent living and pay the constantly rising rents on buildings that remain as dangerously uncared for as the broken sidewalks beneath them. Rumor has it that, in the last decade, there’s been new construction and more investments made in the area. However, I recently watched an online photo exhibit of the South Bronx and it was startling to see just how recognizable it still was.

Poverty invites illness. Growing up, I saw all too many people afflicted by sicknesses that kept them homebound or only able to work between bouts of symptoms. All of us are somewhat powerless when sickness strikes or an accident occurs, but the poor and those working low-paying jobs suffer not just the illness itself but also its economic aftereffects. And in the South Bronx, preventive care remained a luxury, as did dental care, and missing teeth and/or dentures affected both nutrition and the comfort of eating. Doctor’s visits were rare then, so in dire situations people went to the closest hospital emergency room.

Knowledge Is Power

Being a sensitive and curious child, I became a reader at a very early age. We had no books at home, so I went to the library as often as possible. Finding the children’s books then available less than interesting, I began reading ones from the adult section — and it was my good fortune that the librarian turned a blind eye, checking out whatever I chose without comment.

Books made me more deeply aware of the indignities all around me as well as in much of a world that was then beyond me. As I got older, I couldn’t help but see the hypocrisy of a country that loudly proclaimed its love of equality (as taught from the kindergarten pledge of allegiance on) and espoused everywhere values that turned out to be largely unrealized for millions of people. Why, I began to wonder, did so many of us accept the misery, why weren’t we fighting to change such unlivable conditions?

Of course, what I observed growing up wasn’t limited to the South Bronx. Today, such realities continue to be experienced in communities nationwide. Poor and working-class people often have to labor at two or more jobs just to make ends meet (if they’re “lucky” enough to have jobs at all). Many experience persistent anxiety about having enough food, paying the rent, purchasing clothing for their children, or — heaven forbid — getting sick. Such never-ending worries can rob you of the strength even to pay attention to anything more than the present moment. You fret instead about what’s to be on your plate for dinner, how to make it through the day, the week, the month, never mind the year. And add to all of this the energy-sapping systemic racism that people of color face.

During the Vietnam War years, I began organizing against poverty, racism, sexism, and that war in poor white working-class neighborhoods. I asked people then why living in such awful situations wasn’t creating more of a hue and cry for change. You can undoubtedly imagine some of the responses: “You can’t fight city hall!” “I’m too exhausted!” “What can one person do?” “It’s a waste of the time I don’t have.” “It is what it is.”

Many of those I talked to complained about how few politicians who promise change while running for office actually deliver. I did then and do now understand the difficulties of those who have little and struggle to get by. Yet there have been people from poor and working-class communities who refused to accept such situations, who felt compelled to struggle to change a distinctly unjust society.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, though not myself a student, I became a member of Students for a Democratic Society, better known in those years as SDS. I also got the opportunity to work with members of the New York chapter of the Black Panther Party who came together thanks to direct experiences of racism and poverty that had kept so many of them from worthwhile lives. The Panthers were set on doing whatever they could to change the system and were remarkably clear-eyed in their belief that only struggle could bring about such a development.

Mostly young, and mostly from poor backgrounds, their members defied what convention taught: that the leaders of movements usually come from the middle and upper-middle classes. Of course, many then did and still do. Many grew up well-fed, well-sheltered, and safe from hunger or future homelessness. Many also grew up in families where social-justice values were a part of everyday life.

However, there is also a long history of poor and working-class people becoming leaders of struggles against injustice. The Black Panthers were one such group. As I write this, many safety-net programs are under assault from reactionary Republicans who wish to slash away at food stamps and other programs that offer at least modest support for the poor. They have been eager to add work provisions to safety-net programs, reviving the old trope that the poor are lazy or shirkers living off the dole, which couldn’t be further from the truth. They insist on believing that people should lift themselves out of poverty by their own bootstraps, whether they have boots or not.

But poverty isn’t inevitable, as they would have us believe. Strengthening and expanding the safety net would help so many — like those I grew up with in the South Bronx — move into better situations. However, count on one thing: the reactionary Republicans now serving in government and their MAGA followers will never stop pushing to further weaken that net. They only grow more reactionary with every passing year, championing white nationalism, while attempting to ban books and stop the teaching of the real history of people of color. In short, they’re intent on denying people the power of knowledge. And as history has repeatedly shown, knowledge is indeed power.

Which Way This Country?

As the rich grow richer, they remain remarkably indifferent to suffering or any sort of sharing. Even allowing their increasingly staggering incomes to be taxed at a slightly higher rate is a complete no-no. Poor and working-class people who are Black, Latino, white, Asian, LGBTQ, or indigenous continue to battle discrimination, inflation, soaring rents, pitiless evictions, poor health, inadequate healthcare, and distinctly insecure futures.

Like my parents and many others I knew in the South Bronx, they scrabble to hang on and perhaps wonder if anyone sees or hears their distress. Is it a surprise, then, that so many people, when polled today, say they’re unhappy? However, an unhappy, divided, increasingly unequal society filling with hate is also the definition of a frightening society that’s failing its people.

Still, in just such a world, groups and organizations struggling for social justice have begun to take hold, as they work to change the inequities of the system. They should be considered harbingers of what’s still possible. National groups like Black Lives Matter or the Brotherhood Sister Sol in New York’s Harlem organize against inequities while training younger generations of social-justice activists. And those are but two of many civil-rights groups. Reproductive rights organizations are similarly proliferating, strengthened by women angry at the decisions of the Supreme Court and of state courts to overturn the right to an abortion. Climate change is here, and as more and more communities experience increasingly brutal temperatures and ever less containable wildfires (not to speak of the smoke they emit), groups are forming and the young, in particular, are beginning to demand a more green-centered society, an end to the use of fossil fuels and other detriments to the preservation of our planet. Newly empowered union organizing is also occurring and hopefully will spread across the country. All such activities make us hopeful, as they should.

But here’s a truly worrisome thing: we’re also living in a moment in history when the clamor of reactionary organizing and the conspiratorial thinking that goes with it seem to be gathering strength in a step-by-step fashion, lending a growing power to the most reactionary forces in our society. Politicians like Donald Trump and Ron DeSantis, as well as anti-woke pundits, use all too many platforms to preach hatred while working to erase whatever progress has been made. Scary as well is the fantastical rightwing theory of white replacement which preaches (in a country that once enslaved so many) that whites are endangered by the proliferation of people of color.

This march toward a more reactionary society could be stemmed by a strong counteroffensive led by progressives in and out of government. In fact, what other choice is there if we wish to live in a society that holds a promise for peace, equality, and justice?

My political involvement taught me many lessons of victory and defeat but has never erased my faith in what is possible. Consider this sharing of my experiences a way to help others take heart that things don’t have to remain as they are.

I haven’t been back to the South Bronx since my parents died, but as a writer and novelist I still visit there often.

Copyright 2023 Beverly Gologorsky

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Books, John Feffer’s new dystopian novel, Songlands (the final one in his Splinterlands series), Beverly Gologorsky’s novel Every Body Has a Story, and Tom Engelhardt’s A Nation Unmade by War, as well as Alfred McCoy’s In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power, John Dower’s The Violent American Century: War and Terror Since World War II, and Ann Jones’s They Were Soldiers: How the Wounded Return from America’s Wars: The Untold Story.